Tryptophan found in turkey is believed to be the legendary reason why people always doze off for little naps on Thanksgiving Day. In fact, “Tryptophan is an amino acid that can be found in several foods, which include dairy products, soy products, seafood, poultry and beans” (BeneFit from: Tryptophan, 2008) and there is even more tryptophan in cheese and chicken breast than there is in turkey, according to Elder (2009). To debunk the myth, Elder (2009) says, there is not enough tryptophan in your Thanksgiving turkey to tire you out. However, the tryptophan in your turkey is a precursor to calming, feel-good serotonin.

It seems tryptophan in our food is linked to serotonin, and melatonin. Thornton and Whitley (2012) confirmed the synthesis of serotonin and melatonin can be controlled by tryptophan ingestion (p. 40). Interestingly, Esteban, Nicolaus, Garmundi, Rial, Rodríguez, Ortega, EIbars, (2004) found differences in tryptophan ingestion at the beginning of light or dark phases in rats (p. 41). “The administration of L-tryptophan during the light time increased the brain synthesis and metabolism of serotonin. However, at night, tryptophan’s administration led to a smaller increase in the synthesis of serotonin than by day, although the turnover remained unchanged, suggesting that, in the dark phase, serotonin is used as a substrate for melatonin synthesis” (Thornton & Whitley, 2012, p. 40). Esteban et al., (2004) results imply, “The difference between the effects of increased tryptophan intake during light and dark phases suggests that tryptophan hydroxylase activity presents circadian fluctuations which seem to be clock controlled” (p. 41). So, it seems that the legend behind the Thanksgiving naps can in some ways be linked to tryptophan, and tied to our circadian rhythms.

Tryptophan due to its connection to serotonin has been somewhat studied with its role in depression. Parker and Brotchie, (2011) revealed, “There is limited evidence suggesting that depressed individuals, especially those with a melancholic depression, have decreased tryptophan levels. However, results showing a causal contribution or are a consequence of a depressed state remains an open question. Neither the less, the researchers support there is a small database claiming tryptophan preparations benefit people with depressed mood states.”

In conclusion, turkey has tryptophan but other food such as cheese and chicken breast have higher quantities of this amino acid. The amount of tryptophan you eat on Thanksgiving from turkey is not necessarily enough to make you tired, but it could have an impact on your circadian rhythm. The tryptophan you consume impacts your serotonin, and melatonin, which is likely to impact your mood. So therefore, Have A Great Increase of Serotonin on Your Thanksgiving!

P.S. According to The 10 Foods For A Good Night’s Sleep, “Tryptophan works when your stomach is basically empty, not overstuffed, full of protein and not carbohydrates.”

HAPPY THANKSGIVING!!!

References

BeneFit from: Tryptophan. (2008). Cycling Weekly, 32.

Elder, N. (2009). The Question: Does Turkey Make You Sleepy?. Bon Appetit, 54(11), 47.

Esteban, S., Nicolaus, C., Garmundi, A., Rial, R.V., Rodríguez, A., Ortega, EIbars, C. B. (2004). Effect of orally administered L-tryptophan on serotonin, melatonin and the innate immune response. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry, 267, 39-46.

Parker, G., & Brotchie, H. (2011). Mood effects of the amino acids tryptophan and tyrosine. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 124(6), 417-426. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01706.x

The 10 Foods for a Good Night’s Sleep. (2007). Office Solutions, 24(2), 9.

Thornton, S. H., & Whitley, B. L. (2012). Tryptophan : Dietary Sources, Functions and Health Benefits. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

Katy Roth, M.A., CRC

WKPIC Doctoral Intern

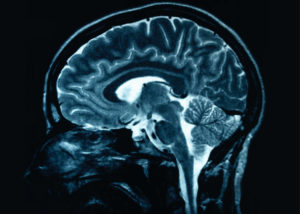

First, the brainstem plays a vital role in REM (rapid eye movement) and NREM (non- rapid eye movement). “The brainstem controls events of REM sleep” Pinel, 2010, pg. 364). REM occurs under the eyelids and was discovered in the 1950’s (Pinel, 2010, pg. 343). Reinoso-Suárez, de Andrés, Rodrigo-Angulo and Garzón (2001) found, “The ventral part of the oral pontine reticular nucleus (vRPO) is a demonstrated site of the brainstem REM sleep-wake cycle, as well as with other brain components responsible for the production of different occurrences related to REM sleep.” Non-REM sleep (NREM) is referred to as slow wave sleep (de Andrés, Garzón, & Reinoso-Suárez, 2011). NREM is vital for standard physical and intellectual functioning and behavior (de Andrés, Garzón, & Reinoso-Suárez, 2011). Further, Villablanca (2004) stated, “Waking can occur independently in both the forebrain and brainstem, but true NREM and REM sleep producing mechanisms exist entirely in the forebrain and brainstem.”

First, the brainstem plays a vital role in REM (rapid eye movement) and NREM (non- rapid eye movement). “The brainstem controls events of REM sleep” Pinel, 2010, pg. 364). REM occurs under the eyelids and was discovered in the 1950’s (Pinel, 2010, pg. 343). Reinoso-Suárez, de Andrés, Rodrigo-Angulo and Garzón (2001) found, “The ventral part of the oral pontine reticular nucleus (vRPO) is a demonstrated site of the brainstem REM sleep-wake cycle, as well as with other brain components responsible for the production of different occurrences related to REM sleep.” Non-REM sleep (NREM) is referred to as slow wave sleep (de Andrés, Garzón, & Reinoso-Suárez, 2011). NREM is vital for standard physical and intellectual functioning and behavior (de Andrés, Garzón, & Reinoso-Suárez, 2011). Further, Villablanca (2004) stated, “Waking can occur independently in both the forebrain and brainstem, but true NREM and REM sleep producing mechanisms exist entirely in the forebrain and brainstem.”