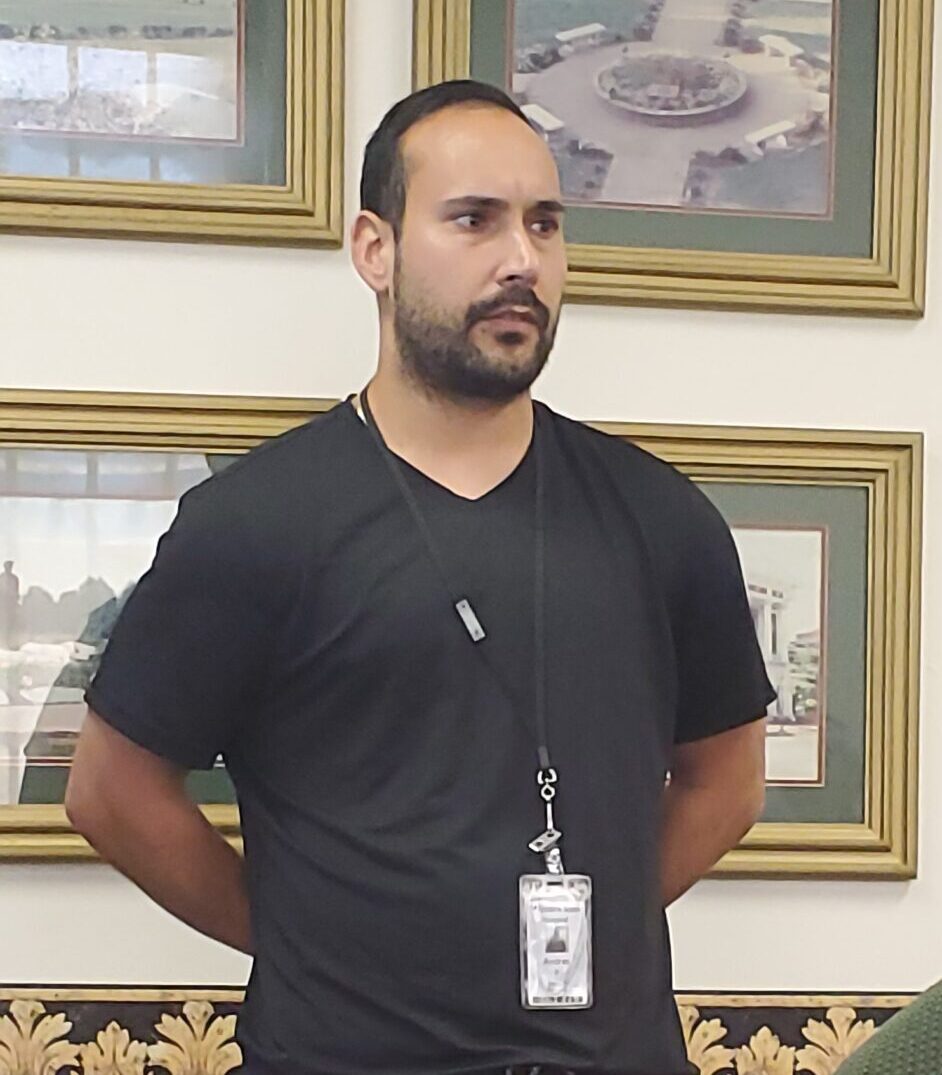

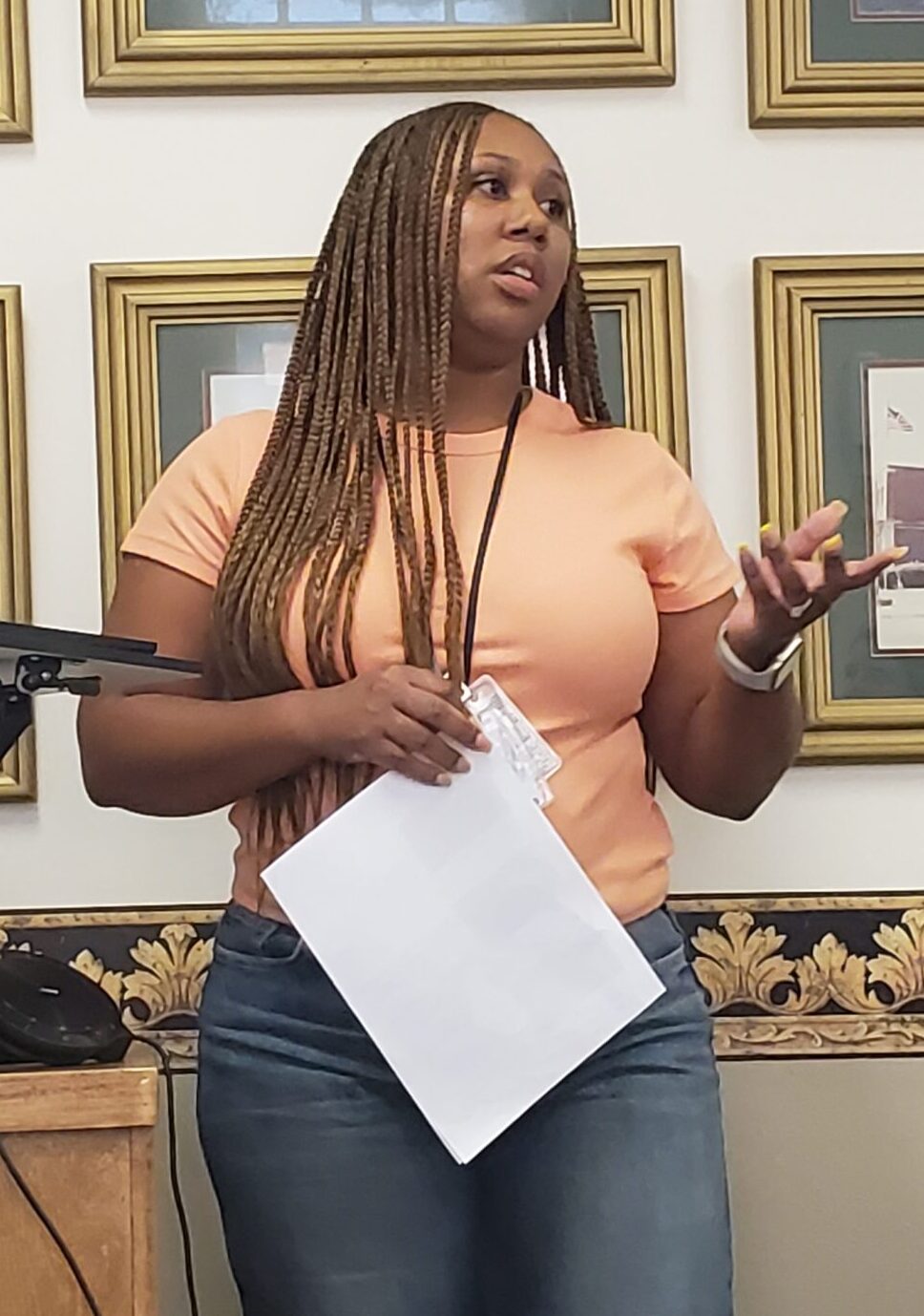

On August 6th, employees from several hospital disciplines were invited to the 2024 Case Study Presentations from our interns. At the beginning of internship year, each intern is assigned a patient whom has been identified as a challenge for our hospital treatment teams. These patient usually have had extensive psychological histories, some going back decades, and multiple admissions, not just at Western State, but other facilities as well. Interns use records to present comprehensive histories, therapy interventions, treatment and testing recommendations to the members of these patients’ treatments teams.

These presentations are enlightening for many who attended. For staff who had not been working at the hospital as long as patients who have been coming here, interns were able to provide detailed background information that is sometimes overlooked in relevance to how it plays a part in patients’ behaviors and illness. These presentations also opened up the discussion of what and how different avenues of therapy may be beneficial.

Many thanks to our interns and Dr. Kerri Anderson for working hard on these presentations. You did a fantastic job!