Big giant hurrah for intern Crystal Henson, for successfully defending her dissertation!

Susan Redmond-Vaught, Ph.D.

Director, WKPIC

Big giant hurrah for intern Crystal Henson, for successfully defending her dissertation!

Susan Redmond-Vaught, Ph.D.

Director, WKPIC

Having a loved one with a mental illness can sometimes feel a lot like trying to love a porcupine. Schopenhauer and Freud have used a metaphor called the Porcupine Dilemma to describe what they feel is the state of the individual in relation to others.

This dilemma suggests that despite goodwill and the desire to have a close reciprocal relationship, porcupines cannot avoid hurting others with their sharp quills for reasons they cannot avoid. This typically results in cautious behavior and unstable relationships.

To work through this dilemma, if you have a loved one suffering with mental illness, consider the following strategies:

Georgetta Harris-Wyatt, MS

WKPIC Doctoral Intern

New research from Sun et al. (2018) has discovered a link between seizures early in development and autism. Notably, these seizures occur during a critical period for the primary auditory cortex, a section of the brain important to language development. It is hypothesized that these seizures disrupt the brain’s development, preventing typical language formation, and since these seizures are occurring during a critical period, this language does not develop unless acted upon (Sun et al., 2018). Fortunately, Sun et al. (2018) found that acting upon the auditory cortex with activity dependent AMPA receptor (AMPAR) following the seizure but before the critical period allowed the brain to develop as expected, suggesting there is a remedy for these seizures if identified early enough.

This study does well in identifying the co-morbid diagnoses of autism or intellectual disabilities and epilepsy or other seizure disorders. By recognizing this correlation, the team was able to recognize the possible connection between seizures interfering with the critical periods of neurodevelopment. With this new research, autism and intellectual disability may become signficnatly less prevalent, however, research will need to continue developing the knowledgebase to assure this outcome. Most notably, it will be important to help determine how best to identify these seizures prior to the critical period. Additionally, research will need to find if other factors contribute to the presentation of autism and intellectual disability to continue our understanding of these causative factors and how they contribute to the development of these disorders.

References:

Sun, H., Takesian, A.E., Wang, T.T., Lippman-Bell, J.J., Hensch, T.K., Jensen, F.E. (2018). Early seizures prematurely unsilence auditory synapses to disrupt thalamocortical critical period plasticity. Cell Reports, 23 (9), 2533. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.04.108

Michael Daniel, MA, LPA (temp)

WKPIC Doctoral Intern

The concept of vicarious group trauma is relevant for Jewish individuals because people who did not directly experience the Holocaust can still exhibit signs and symptoms of trauma exposure related to this event. Fuhr (2016) studied historical trauma related to Jewish individuals who lived in Britain. The researcher defined vicarious group trauma as, “A life or safety-threatening event or abuse that happened to some members of a social group, but is felt by other members as their own experience because of their personal affiliation with the group.” The research noted that these individuals can experience anxiety, perceptions of threat and hypervigilance simply due to their identification to the group, due to the magnitude of the trauma inflicted upon the group as a whole.

Cohn and Morrison (2017) found that in their sample, the trauma of the participants’ grandparents’ Holocaust experience impacted their own affective experience, their sense of connection to family history, their understanding of being different than others, and their political and ethnic values. Further, Abrams (1999) reported that when conducting therapeutic interventions, silence was a significant clinical feature in Jewish families contending with traumatic experiences. Survivors of a major historical trauma who remain silent are often condemned to desiccated existence, whereas those who speak out are susceptible to somatic consequences, psychosis, or even suicide (Rosenblum, 2009).

When conducting psychological treatment with people who are Jewish, it is important to be mindful of the historical trauma Jewish individuals have faced, and the fact that they may define themselves in collective manners as a part of a group of their ancestors who survived the Holocaust (Cohn & Morrison, 2017). Additionally, it is important to encompass thoughts about the effect on the individual level, the family level, and the environmental level, and confront patterns of the family that maintain burnout in the environment, as well as bring about appropriate structural change within the family to allow for safe expression and healing (Abrams, 1999). Abrams (1999) also noted that fostering open communication between older generations and younger generations can provide critical understanding and relief to families, lessening these collective effects.

References

Abrams, M. (1999). Intergenerational transmission of trauma: Recent contributions from the literature of family system approaches to treatment. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 53 (2), 225-231.

Cohn, I. G., & Morrison, N. M. (2017). Echoes of transgenerational trauma in the lived experiences of Jewish Australian grandchildren of holocaust survivors. Australian Journal Of Psychology, doi:10.1111/ajpy.12194

Fuhr, C. (2016). Vicarious Group Trauma among British Jews. Qualitative Sociology, 39(3), 309-330. doi:10.1007/s11133-016-9337-4

Rosenblum, R. (2009). Postponing trauma: The dangers of telling. The International Journal Of Psychoanalysis, 90(6), 1319-1340. doi:10.1111/j.1745- 8315.2009.00171.x

Katy Roth, M.A., CRC

WKPIC Doctoral Intern

Historical trauma is relevant to examine regarding African Americans because those who never experienced the traumatic stressor themselves, such as children and descendants of people who experienced race-based genocide/slavery, can still exhibit signs and symptoms of trauma. In the United States alone, African Americans have experienced over 350 years of oppression, generations of discrimination, slavery, colonialism, imperialism, racism, race-based segregation and poverty (Ross, n.d.).

In addition, African Americans currently are exposed to frequent and even multiple daily microaggressions, which are defined as, “Events involving discrimination, racism, and daily hassles that are targeted at individuals from diverse racial and ethnic groups” (Michaels, 2010). “Racial microaggressions are brief and commonplace, and include daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults toward people of color,” (Sue, Capodilupo, Torino, Bucceri, Holder, Nadal, & Esquilin, 2007). The impact of historical and generational trauma can affect people of color such that internal impressions/views of self begin to skew, and negative behavior and emotions such as anger, hatred, and aggression become self-inflicted, as well as imposed on members of one’s own group (Ross, n.d.).

Stigma related to mental illness also impacts views on mental health and help-seeking behaviors because African Americans who received services, as well as those with no prior experience with mental health services, associated these supports with embarrassment and shame (Thompson, Bazile & Akbar 2004). The researchers also found that African American participants in mental health services have mistrust around mental health practitioners, and that it may be challenging for psychologists and psychotherapists to be free of the attitudes and the beliefs of the larger society, especially due to stereotypes.

Asbury, Walker, Belgrave, Maholmes, and Green (1994) found that perceptions of provider competence, self-esteem, emotional support, and attitudes toward seeking services were significant predictors of seeking service. In addition, racial similarity, perception of provider competence, and perceptions of the service process determined continued participation. Pole, Gone, and Kulkarni, (2008) and Sue (1998) found that overall, African-Americans attended average to fewer sessions (underutilize services), as well as terminated from services earlier than European Americans.

When conducting psychological interventions with African Americans it is important to be mindful of their cultural beliefs, as well as current oppression (stereotypes) faced by this population, and to be culturally sensitive to the issues and experiences that the African-American community has historically confronted, and continues to experience (Ross, n.d.). When conducting psychological treatment with people of color, it is important to be mindful of the historical and generational trauma African Americans have faced, as well as keeping in mind how internal oppression can impact their views on mental health and help-seeking behaviors.

References

Asbury, C. A., Walker, S., Belgrave, F. Z., Maholmes, Green, L. (1994). Psychosocial, cultural, and accessibility factors associated with participation of African Americans in rehabilitation. Rehabilitation Psychology, 39, 113-121.

Michaels, C. (2010). Historical trauma and microagressions: A framework for culturally- based practice. Children, Youth & Family Consortium’s Children’s Mental Health Program. Retrieved from http://www.cmh.umn.edu/ereview/Oct10.html

Pole, N., Gone, J. P., & Kulkarni, M. (2008). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Among Ethnoracial Minorities in the United States. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice, 15(1), 35-61. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.2008.00109.x

Ross, K. (n. d). Impacts of historical trauma on African Americans and its effects on help-seeking behaviors. Presentation. Missouri Psychological Association.

Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271-286.

Sue, S. (1998). In search of cultural competence in psychotherapy and counseling. American Psychologist, 53(4), 440-448.

Thompson, V. L., Bazile, A. & Akbar, M.D. (2004). African American’s Perceptions of Psychotherapy and Psychotherapists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 35, 19-26.

Katy Roth, M.A., CRC

WKPIC Doctoral Intern

Native Americans have been facing psychological consequences of genocide for over 400 years. Due to colonization and military attacks, Native Americans have been subjected to one of the most systemic and brutal ethnic cleansing operations in history. They were relocated to penal colonies, neglected, starved, forbidden to practice their religious beliefs, and their children were taken away from them and reeducated so that much of their language, culture and kinship patterns were lost (Whitbeck, Adams, Hoyt, & Chen, 2004). In addition, the researchers note that the threats of their lives and cultures being obliterated has become progressive, increasing as each generation passes away. One elder noted, “I feel bad about it. Tears come down. That is how I feel. I feel weak. I feel weak about how we are losing our grandchildren.”

Native Americans still are faced with daily reminders of this violent erasure of self and community, such as reservation living, encroachment on their reservation land, loss of language, loss of traditional practice, and loss of healing practices (Whitbeck, Adams, Hoyt, & Chen, 2004). The Indian Health Service (1995) noted that Native American alcoholism death rate was 5.5 times the national average. One can argue that this population is drinking as a means of coping with the historical and generational trauma, as well as the daily reminders of the trauma they experience. Whitbeck, Adams, Hoyt, and Chen, 2004 supported this theory, indicating that daily reminders of ethnic cleansing coupled with persistent discriminations are the keys to understanding historical trauma among Native people.

When conducting psychological treatment with this population it is important to be mindful of the historical and generational trauma Native Americans have faced, as well as keeping in mind the role their culture plays. Brave Heart and DeBruyn (1998) highlight that when conducting psychological treatment it is important to recognize that Native Americans incorporate spiritual empowerment and utilize traditional healing ceremonies, which have a natural therapeutic and cathartic effect for spiritual, physical and emotional healing. Many tribes need to conduct specific grief ceremonies, not only for recent deaths, but also historical traumas, including but not limited to the loss of sacred objects being repatriated, mourning for human remains of ancestors, loss of rights to raise children in their cultural norms, and loss of land. Bridging both evidence-based treatment (EBT) and culturally sensitive approaches in this population appears advantageous. Gone (2009) found, “Both in Northern Algonquian and other Native community contexts, the therapeutic emphasis often remains on healing rather than treatment.” McCabe (2007) supported this finding, indicating that Native healing goes beyond the meaning of distress and coping, to fostering a robust sense of well-being, a strong Aboriginal identification, cultural reclamation, purposeful living and spiritual well-being. Native Americans may not be fond of formal outcome assessment or therapeutic interventions, and find it a distraction from the provision of services ( (Gone, 2011).

References

Brave Heart, M., & DeBruyn, L. (1998). The American Indian holocaust: healing historical unresolved grief. American Indian & Alaska Native Mental Health Research: The Journal Of The National Center, 8(2), 56-78.

Gone, J. P. (2009). A Community-Based Treatment for Native American Historical Trauma: Prospects for Evidence-Based Practice. Journal Of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 77(4), 751-762. doi:10.1037/a0015390

Gone J. P. (2011). The red road to wellness: Cultural reclamation in a Native First Nations community treatment center. American Journal of Community Psychology 47(1–2):187–202

Indian Health Service. (1995). Trends in Indian health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Washington, DC.

McCabe, G. H. (2007). The healing path: A culture and community-derived indigenous therapy model. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 44, 148– 160.

Whitbeck, L. B., Adams, G. W., Hoyt, D. R., & Chen, X. (2004). Conceptualizing and Measuring Historical Trauma Among American Indian People. American Journal Of Community Psychology, 33(3/4), 119-130.

Katy Roth, M.A., CRC

WKPIC Doctoral Intern

Historical trauma is relevant to examine regarding the Japanese population in the United States, because those who never experienced the traumatic stressor themselves, such as children and descendants, can still exhibit signs and symptoms of trauma. “During World War II, the United States confined 120,000 Japanese Americans in camps based solely on their Japanese heritage and two thirds of those forced to live in the camps were United States Citizens,” (Nagata, Kim, & Nguyen, 2015.) In addition, the researchers noted that even though the United States was also at war with Germany and Italy, neither German Americans nor Italian Americans were subjected to mass incarceration, like the Japanese Americans.

When conducting psychological treatment with this population it is important to be mindful of the historical and generational trauma Japanese individuals have faced, and to note that, “Even though the incarceration assaults on identity represented a cultural trauma, Japanese Americans did not process them as a collective group. Instead, the impacts were contained primarily at the individual trauma level, during and after the war,” (Nagata, Kim, & Nguyen, 2015.) In addition, the researchers stated, after the Japanese Americans experienced incarceration in camps, they attempted to cope by silence to repress the incarceration trauma for more than three decades. Laub and Auerhahn (1984) supported Nagata, Kim, and Nguyen (2015) and stated, “The more profound the outer silence exhibited by a Japanese individual, the more extensive was the inner impact of the event experienced (p. 154).”

In many cases, the lack of communication about the interment created a sense of foreboding for the Sansei as they grew older, and ultimately increased the curiosity about the camps, as well as heightened their sense of parental trauma (Nagata, 1991). A participant described the topic of internment as a forbidden topic that family tiptoed around, like a family scandal. It is important when conducting therapy with Japanese individuals to explore the role of this silence, not only on an individual level but a familial level, and to explore the client’s interpretation of that silence. In addition, this population may experience lower levels of self-esteem and identity issues stemming from the historical trauma, which may need to be considered in current psychological treatment. According to Nagata (1991), after the camps, many Nisei felt particularly pressured to demonstrate their worth after being rejected by their country, and their Sansei children were also expected to be the best and acquire the respect of others. Further, while Sansei today have more opportunities accessible to them than their Nisei parents, the camp experience of their parents may continue to affect their sense of ethnic identity, resulting in issues of identity.

Narrative Therapy may be beneficial when working with this population because it will allow the therapist to evaluate the stories of the client and can serve several functions in clinical practice: (1) to “make the latent manifest,” (2) to “help construct a unifying narrative, “and (3) to “reconstruct a more useful and coherent interpretation of past events and future projects than the client’s present narrative” (Polkinghorne, 1988, p. 178). Family therapy is also advantageous for this population because, “The focus of the family work is to unburden relationships by encouraging dialogues among family members whereby protected, hidden, and even unconscious conflicts of loyalty, obligations, myths, and legends can surface and be examined” (Miyoshi, 1980, p. 41).

References

Laub, D. & Auerhahn, N.C. (1984). Reverberations of genocide: Its expression in the consciousness and unconsciousness of post-Holocaust generations. In S. A. Lueland P. Marcus (eds.), Psychoanalytic reflections on the Holocaust (pp. 151-167). New York: KTAV Publishing House.

Miyoshi, N. (1980). Identity crisis of the Sansei and the American concentration camp. Pacific Citizen, December 19-26, 91, pp. 41-42, 50, 55.

Nagata, D. K. (1991). Transgenerational Impact of The Japanese- American Internment: Clinical Issues in Working With Children of Former Internees. Psychotherapy, 28(1), 121-128.

Nagata, D. K., Kim, J. J., & Nguyen, T. U. (2015). Processing Cultural Trauma: Intergenerational Effects of the Japanese American Incarceration. Journal Of Social Issues, 71(2), 356-370. doi:10.1111/josi.12115

Polkinghorne, D. E. (1988). Narrative knowing and the human sciences. New York: State University of New York Press.

Katy Roth, M.A., CRC

WKPIC Doctoral Intern

In the last 40 years, there has been an increased interest and usage of mindfulness based therapy approaches to treat a variety of mental disorders. Mindfulness activities teach the individual to be aware of the experience by purposefully paying attention to the present moment in a non-judgmental way (Kabat-Zinn & Hahn, 1990). Some of the most common therapeutic approaches that utilize mindfulness activities are Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction, Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, and Dialectical Behavior Therapy.

Emerging research now indicates that mindfulness based therapy may be a beneficial treatment approach for psychosis. Jacobsen, Morris and Johns (2010) studied the feasibility of using mindfulness based therapy groups on an inpatient unit. All participants in this study were currently on an inpatient unit that specializes in working with individuals with severe psychosis. Eight patients completed the study and the average length of contact with mental health services for these patients was 12 years (Jacobsen, et al., 2010).

Emerging research now indicates that mindfulness based therapy may be a beneficial treatment approach for psychosis. Jacobsen, Morris and Johns (2010) studied the feasibility of using mindfulness based therapy groups on an inpatient unit. All participants in this study were currently on an inpatient unit that specializes in working with individuals with severe psychosis. Eight patients completed the study and the average length of contact with mental health services for these patients was 12 years (Jacobsen, et al., 2010).

In the study, group sessions met for a one hour session over the course of 6 weeks. Group session format was consistent across all sessions to provide familiarity and to accommodate those who were unable to attend all sessions (Jacobsen, et al., 2010). Each session included a two 10-minute mindfulness breathing exercises followed by group discussion based on protocols used by Chadwick and colleagues (2005). Discussions included the rationale for mindfulness therapy, how mindfulness can be utilized in distressing situations, and recent experiences with mindfulness.

The results of this study indicated that mindfulness based therapy groups are a feasible treatment option for individuals with psychosis who are currently at an inpatient hospital. Specifically, the study found individuals with psychosis do well in short sessions where they can reflect on personal experiences (Jacobsen, et al., 2010). The study noted that for a group to be successful on an inpatient unit is to ensure all members of the interdisciplinary team have an understanding of the skills to help promote patient participation outside of the group setting.

References

Chadwick, P., Newma-Taylor, K., & Abba, N. (2005). Mindfulness Groups for People with Psychosis. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 33, 351-359.

Jacobsen, P., Morris, E., Johns, L., & Hodkinson, K. (2010). Mindfulness Groups for Psychosis; Key Issues for Implementation on an Inpatient Unit. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 39, 349-353.

Kabat-Zinn, J., & Hanh, T. N. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. Delta.

Anissa Pugh, MA, LPA

WKPIC Doctoral Intern

At least 85% of mental health consumers report exposure to trauma at some point in their lives. A vast majority of these consumers lack the appropriate coping skills to manage their emotions and reactions appropriately, traditionally resulting in the use of restraints, isolation or coercion when in an inpatient setting. The shift to trauma-informed care requires staff working with these patients to understand that the individual is doing the best they can, with the coping skills they have based on their life experiences. Trauma-informed care involves including consumers in their treatment and allowing them to have a voice in what they feel would be of most benefit. Below are some basic ways to create a trauma-informed treatment environment in an inpatient setting:

Chandler, G. (2008). From Traditional Inpatient to Trauma-Informed Treatment: Transferring Control From Staff to Patient. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 14(5), 363-371. doi:10.1177/1078390308326625

Crystal Henson, MA

Doctoral Intern

It’s become increasingly common for people to need glasses to improve their vision (Marczyk, 2017). For many, this increasing issue has been puzzling since, years prior to the advent of glasses, people were able to survive without corrected vision. Many theories have been examined. Some have asserted that, with corrective lenses, bad vision is no longer a hindrance to survival and no longer a deterrent evolutionarily (Marczyk, 2017).

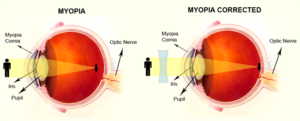

Others have hypothesized that our concerns stem from an infectious component not yet identified. However, new research asserts it rises from our behavior. As technology has changed, our behaviors have changed. We are spending increasing amounts of time indoors reading and watching screens. In the past, many have asserted that poor eyesight is a common predictor of intelligence, citing eye strain related to reading or screen-time as a major predictor for nearsightedness. However, nearsightedness may not be related to eye strain but, instead, the increased time we are spending inside (Marczyk, 2017). When examining children who spend most of their time indoors, researchers found they had a greater likelihood of developing myopia, or nearsightedness, than their peers who spent more time outside. In healthy eyes, light focuses on the back of the retina (National Eye Institute, 2017). In eyes with myopia, the light is focused before it hits the retina resulting in a blurry image.

The new hypothesis suggests limited exposure to sunlight during development results in more difficulties with nearsightedness as the eye never learns to adapt to high exposure to light (Marczyk, 2017).

References

Marczyk, J. (2017). Why do so many humans need glasses?: Mismatched modern and ancestral environments, and their consequences. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/pop-psych/201706/why-do-so-many-humans-need-glasses

National Eye Institute. (2017). Facts about myopia. Retrieved from https://nei.nih.gov/health/errors/myopia

Michael Daniel, MA, LPA (temp)

WKPIC Doctoral Intern