It’s become increasingly common for people to need glasses to improve their vision (Marczyk, 2017). For many, this increasing issue has been puzzling since, years prior to the advent of glasses, people were able to survive without corrected vision. Many theories have been examined. Some have asserted that, with corrective lenses, bad vision is no longer a hindrance to survival and no longer a deterrent evolutionarily (Marczyk, 2017).

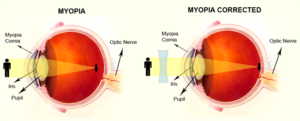

Others have hypothesized that our concerns stem from an infectious component not yet identified. However, new research asserts it rises from our behavior. As technology has changed, our behaviors have changed. We are spending increasing amounts of time indoors reading and watching screens. In the past, many have asserted that poor eyesight is a common predictor of intelligence, citing eye strain related to reading or screen-time as a major predictor for nearsightedness. However, nearsightedness may not be related to eye strain but, instead, the increased time we are spending inside (Marczyk, 2017). When examining children who spend most of their time indoors, researchers found they had a greater likelihood of developing myopia, or nearsightedness, than their peers who spent more time outside. In healthy eyes, light focuses on the back of the retina (National Eye Institute, 2017). In eyes with myopia, the light is focused before it hits the retina resulting in a blurry image.

The new hypothesis suggests limited exposure to sunlight during development results in more difficulties with nearsightedness as the eye never learns to adapt to high exposure to light (Marczyk, 2017).

References

Marczyk, J. (2017). Why do so many humans need glasses?: Mismatched modern and ancestral environments, and their consequences. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/pop-psych/201706/why-do-so-many-humans-need-glasses

National Eye Institute. (2017). Facts about myopia. Retrieved from https://nei.nih.gov/health/errors/myopia

Michael Daniel, MA, LPA (temp)

WKPIC Doctoral Intern